| |

Whistle Stop Christmas In Cleburne, the Whistle Stop Christmas Lights wow visitors on an annual basis. The main draw for this county-wide event is the 11 acres of Christmas lights covering Hulen Park which stay lit for the whole month of December. | |

| Hill Country Regional Lighting Trail The Texas Hill Country communities of Boerne, Burnet, Dripping Springs, Fredericksburg, Goldwaite, Johnson City, Llano, Marble Falls, New Braunfels, Round Mountain and Wimberley are all part of the Hill Country Regional Lighting Trail. Each of these towns offer visitors dazzling light displays among the rolling hills of Central Texas. | |

| Santa's Wonderland College Station's Santa's Wonderland features 2.5 million lights spread across 40 acres and is one of the largest holiday theme parks in the nation. | |

| Holiday Trail of Lights Probably the most famous Texas light trail, Jefferson's Holiday Trail of Lights features an enchanted forest, life-size gingerbread house, candlelight tour of homes and more - not to mention plenty of lights. |

Monday, November 28, 2011

Texas Holiday Light Festivals (Just A Few, Not All)

The Wonders of Olive Oil

Olive Oil Health Benefits, Types, Selection, Storage, Cooking Tips

By Laura Dolson, About.com Guide

Updated November 28, 2011

Photo © Olga Lyubkina

Photo © Olga LyubkinaAds

Italian Epicure SpecialsFinest Cyber Groceria & Salumeria Prosciutto Parma & Formaggio GiftsItalianFoodImports.com

Top 10 Cooking OilsLearn which cooking oils are best for your health and why.www.dLife.com

Signs Of High CholesterolLearn The Signs Of High Cholesterol & Get Tips On Lowering Cholesterol.Pebble.com/Cholesterol

Ads

Lower Your LDL LevelGet Tips on How to Manage and Reduce Your High Cholesterol Here.merckengage.com

Food To Lower CholesterolWhich Foods Help Lower Your LDL? Find 3 Easy Recipes To Get Healthy!StayingFit.com

Health Benefits of Olive Oil

Plugging "olive oil" into the PubMed search engine (the database of medical and health-oriented research) yields over 6000 studies. Not many specific foods get this much attention in the medical literature, and there are good reasons that olive oil is being so well-studied. It is loaded with polyphenols and other phytonutrients (many of which are antioxidants), and is high inmonounsaturated fats. Here are some of the probable health benefits of olive oil: 1. Anti-Inflammatory Effects - There is a lot of talk about anti-inflammatory diets these days (since so many chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and arthritis have been linked to chronic inflammation in our bodies), but few foods have actually been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects in the body. There is mounting evidence that extra virgin olive oil may be one of those foods, with quite a number of studies documenting lower levels of chemicals associated with inflammation (C-reactive protein and others) when olive oil is added to the diet. One to two tablespoons of virgin or extra-virgin olive oil per day has been shown to produce these anti-inflammatory effects in the body. 2) Antioxidant Effects - It turns out that some of the compounds in olive oil (e.g. hydroxytyrosol and one with an even longer name abbreviated DHPEA-EDA), are among the strongest antioxidant chemicals discovered in food so far. It is thought that antioxidant compounds can protect our cells from damage in a number of ways. Primarily it is to combat a type of damage called "oxidative stress", which occurs in the normal course of cell functioning and as a result of other types of wear and tear on the body (e.g. radiation of various types). There is a wide variety of antioxidants in our bodies to control this damage, some of which comes from the foods we eat, and olive oil has been shown to be helpful in this way. 3) Cardiovascular Protection - Olive oil probably helps protect our hearts and arteries in a wide variety of ways. At least one of the polyphenols (hydroxytyrosol) may even help protect our arteries on a genetic level. Oxidative stress damages our cardiovascular systems, so the polyphenols and other antioxidants can help in that way, and the anti-inflammatory effects also help our hearts and arteries. Some of the polyphenols can prevent blood platelets from clumping together, which is one of the causes of heart attacks. The monounsaturated fats in olive oil may have a positive effect on cholesterol profiles, and may even help lower blood pressure. Additionally, substances in olive oil can also protect some of the components of blood itself, including the red blood cells and LDL cholesterol, which is mostly a problem when it becomes oxidized. check on allowed FDA claim. 4) Cancer Protection - Since we so often associated olive oil with lowering our risk for heart disease, it may surprise you to learn that there is a fair amount of research showing a lowering of the risk of some cancers as well, particularly those of the digestive tract and breast (although there is preliminary evidence for many others, even leukemia). The mechanism is thought to be at least partly from the antioxidants' protecting the DNA in the cells. Other preliminary research suggests that consuming olive oil could protect us from cognitive decline, osteoporosis, and even the balance of bacteria in our guts.One important note: Many of the health-giving phytonutrients are present in high amounts only in virgin and extra-virgin olive oil.What is Extra-Virgin Olive Oil and Why is it Better for Us?

Virgin olive oil is extracted from the olives purely by mechanical means (either by pressing or spinning the olives after they are mashed into a paste). No chemical processing is allowed in producing virgin olive oil. The best of the virgin oil is classified as "extra-virgin", which has very superior characteristics including very low rancidity, and has the best flavor. It also has the highest level of polyphenols and other phytonutrients. Plain virgin olive oil also has high levels of these compounds, and a rancidity of less than two percent. Other olive oil classifications include refined olive oil, which is chemically processed to remove "impurities", which unfortunately include some of the phytonutrients. The good things about refined oil are that it has a more neutral flavor (valuable when cooking some things) and a higher smoke point. The "impurities" in virgin olive oil begin to burn at 300 degrees F, producing smoke and bitter flavors, as well as lessening the health benefits. A product labeled simply "olive oil" is a blend of refined and virgin olive oils. "Olive pomace oil" is obtained by a chemical process to get the last drops of oil out of the olive paste. U.S. and Australian studies have previously shown that much of the imported olive oil sold in the U.S. and Australia as "extra-virgin" did not meet those standards. However, more recently the USDA has issued voluntary standards similar to those in Europe partially in the attempts to standardize both domestic and imported oil in the United States.Selection and Storage

Olive oil goes rancid more slowly than some other oils (presumably due to the high antioxidant content), but it does degrade over time. The oil itself will go rancid and the polyphenols and other compounds will also break down. (Extra-virgin olive oil will turn to virgin olive oil in a glass bottle exposed to light at room temperature.) The main ways to avoid this are to protect the oil from light and heat. Some tips: - Buy olive oil in dark glass bottles (or harder to find metal containers)- Try to buy from a store that has a rapid turnover - no dusty bottles sitting on the shelves for months.- The annual olive harvest is in autumn for most varieties. Look to see if there is date on the label, and try to get the freshest oil you can. - Store in a dark cool cupboard, or (better yet) the refrigerator until ready to use, then transfer the amount you will use in a week or two to a dark glass bottle. Olive oil in the refrigerator will solidify, but will "melt" again at room temperature.How to Get More Olive Oil into Your Diet

Want to try to get that recommended 1-2 tablespoons of olive oil into your diet? The first thing we think of when using olive oil is salad dressing, which is a great start. Too often people cover their salads with dressings made with soy oil or other oils high in omega-6 fats. But it's so much better to use an oil with such wonderful health benefits as virgin or extra-virgin olive oil. (See Healthy Salad Dressings for purchasing and recipes). For other ideas, Greece is a great place to turn to, as a Greek person typically consumes 26 liters of olive oil in a year! (Think what this means: those calories are NOT other things which would be less healthful such as processed foods and less healthful fats. Plus, olive oil is usually eaten with healthy foods such as vegetables and seafood.) Greeks drizzle olive oil over almost everything -- almost all vegetable, meat, and seafood dishes. They also cook vegetables in it, marinate meats, and preserve vegetables such as red peppers and dried tomatoes in it. The foods of other Mediterranean countries, from Spain and Italy to Morrocco and the countries of the Middle East, also use a lot of olive oil in their foods. The rest of the world would do well to emulate them.Posted via email from WellCare

How Can I Tell if God is Really Telling Me Something?

| Q: How can I tell if God is telling me to do something, or if I'm just imagining it must be OK with God, but it isn't? I want to do what's right, but sometimes I think God told me to do something, but later I realize He probably didn't. -- Z.J. A: The most important thing God wants you to know is that He loves you and knows what is best for you -- because He does, He wants to show you His will. He doesn't want us to stumble around making bad decisions all the time. When we do, we not only miss His perfect plan for our lives but we also end up suffering the consequences of our foolish ways. What is God's will for you? God's will first of all is that you would commit your life to Jesus Christ, repenting of your sins and by faith asking Him to come into your life as your Savior and Lord. Don't miss this step! Jesus said, "My Father's will is that everyone who looks to the Son and believes in him shall have eternal life" (John 6:40). If you have never done so, ask Christ to come into your life today. Then God's will is for you to become more like Jesus, by turning from sin and seeking (with His help) to be pure and loving -- even as He is. When our goal in life is to follow Him, our selfish and sinful desires begin to fade. Finally, God wants you to follow Him every day. Pray about the decisions you make; ask if what you're seeking is honoring to Christ; avoid anything that might make others doubt the reality of your faith. If you aren't certain something is God's will, then avoid it. Remember: God's will is always best. |

Posted via email from Religion

Sunday, November 27, 2011

The Simple Blessings of Christmas

| by Mark Gilroy |

| Norman Vincent Peale, noted minister and author from the previous century, tells the story of a young girl from Sweden spending Christmas in big, bustling New York City. She was living with an American family and helping them around the house, and she didn't have much money. So she knew she couldn't get them a very nice Christmas present - besides, they already had so much, with new gifts arriving every day. With just a little money in her pocket, she went out and bought an outfit for a small baby, and then she set out on a journey to find the poorest part of town and the poorest baby she could find. At first, she received only strange looks from passersby when she asked them for help. But then a kind stranger, a Salvation Army bell-ringer, guided her to a poor part of town and helped her deliver her gift. On Christmas morning, instead of giving them a wrapped present, she told the family she served what she had done in their name. Everyone was speechless, and everyone was blessed - the girl for giving, the wealthy family for seeing others with new eyes, and the poor family for receiving an unexpected gift. All of us have opportunities both large and small to show kindness, especially at Christmastime. We can help strangers by delivering gifts to needy kids or serving homeless families at a soup kitchen. Or we can simply look for everyday ways to be kind, like allowing someone to go ahead of us in a lengthy line at the department store, or giving that bell-ringer a little change and a few encouraging words. Maybe it's because we're in gift-giving mode anyway that giving to others becomes so important at Christmas. Or because we're more aware of our families and friends and communities. Or maybe it's because two thousand years ago, the earth received the most perfect, most loving gift of all, helping us to understand true kindness. Whatever the reason, don't let Christmas pass you by without showing kindness to someone. Because it is truly more blessed to give than to receive. |

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Doing a Double Take on Double-Talk

Rob Kyff

Word pairs are the bread and butter of English. We love, for instance, to say that price gougers are charging us an "arm and a leg," even though losing just one of these appendages would be bad enough. During a downpour, it rains not only "cats" but also "dogs," and describing a tingling sensation summons both "pins" and "needles."

But sometimes our use of these phrases seems to be, well, "touch and go." Consider the widespread mis-rendering "a-carrot-and-a-stick approach" as "a carrot-on-a-stick approach," a mistake that entirely destroys the allusion to motivating a stubborn donkey with both reward andpunishment. In some cases, people have simply forgotten what these doublets originally described. In previous columns, I've traced "touch-and-go" to sailing ships that scraped their keels on reefs or sandbars but sailed on without much loss of speed, and "cut and run" to cutting loose the ship's anchor (or cutting the ropes that unfurl the sails) to make a quick getaway. Even the origin of "cut-and-dry" isn't cut and dried. Some say this phrase originally referred to processing timber or firewood, while others swear it began with meat, fish or tobacco. Who knows? And what of the "rack" in "rack and ruin," the "cranny" in "nook and cranny" and the "beck" in "beck and call"? "Rack" is a variation of "wrack," an old word for wreckage or destruction in general. The original meaning of "rack" was something driven by the sea, so "rack" came to refer to anything washed up on shore, from dried seaweed to a wrecked ship. The phrase "rack and ruin" appeared in written English as early as the 1500s. Though we rarely use "cranny" without the accompanying "nook," a "cranny" is a small break or slit or an obscure corner. It comes from the Middle French "cren, cran," meaning a notch, as in "crenellation." Though both "nook" and "cranny" are relatively old words, they didn't team up in print until the 1830s. The "beck" in "beck and call" is an old term for a wordless gesture of command, such as a hand or forefinger motioning you to come here or go there. "Beck" is a clipped form of "beckon" and is related to the German word for "signal," which also gives us "beacon." The phrase "beck and call," meaning being subject to both physical and verbal instructions, first appeared in print during the 1870s.Friday, November 25, 2011

THE VISION THING

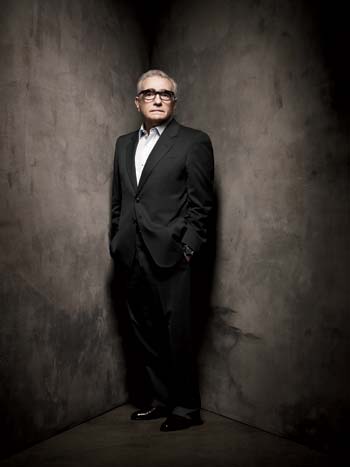

Photo by Art Streiber

BY RICK TETZELI

AT 69, AN AGE WHEN MOST HOLLYWOOD DIRECTORS have been packed off after a hollow cavalcade of plaudits, roasts, and nostalgic fetes, Martin Scorsese is once again panicked about hitting a deadline. His new movie is Hugo, a 3-D children's movie being released by Paramount Pictures this Thanksgiving weekend, and Scorsese has never before directed in 3-D, nor, God knows, made anything resembling a kid flick. But this is what life is like for Marty, as everyone calls him. The director has achieved the trifecta of a fulfilling, creative life: enough money to do only what truly interests him, enough freedom to attack those projects in a way that is satisfying, and enough appreciation from his peers to tame--just slightly, just ever so slightly--the neurotic beast of self-doubt. After 22 movies, five commercials, 13 documentaries, a handful of music videos, three children, five wives, and 25 studios; after insolvency and misery, after box-office failures and years of going unappreciated; after the one Oscar and all the others he should have won, Marty Scorsese has earned the right that every creative person dreams of: the right never to be bored. And what all this adds up to in his case, what this really means to this particular man, is that he has earned the right to continue to fret every little detail in the world well into the next decade and for as long as he cares to make movies.

So as he sits down for the filmed part of a fastcompany.com interview in his office screening room, a comfortable unostentatious cave surrounded outside by posters of classic films likeThe Third Man, Citizen Kane, and Ladri di Biciclette (The Bicycle Thief), Hollywood's eminence grise starts off by wanting to get something straight: "Let me ask you: Do I look like Quasimodo? Am I sitting too far down in the chair? The shoulders on this jacket, against these chairs, they can scrunch up so I look like Quasimodo. Okay, is this good?" Yes, Mr. Scorsese. And how are you feeling today?

"I'm good. I'm tired. I'm tired, but in a good way. There's just so much to do. What I'm worried about is, is there confusion in the film? Because there's so many things going on, especially in a movie like this, in 3-D. There's the color timing; Bob Richardson has done the film but he's in Budapest right now shooting another film, and he's got to get the timing right, but he's doing it through Greg Fisher who's living here now, but originally Greg did it with Bob in England, so there's that problem. Rob Legato is living here now for the special effects--he doesn't live here, but he's here in New York till the picture's finished. These special effects are hard! Some take 89 days to render--89 days to render! And what if you don't like it when it comes back? I tell them at a certain point, you've gotta tell me, you've got to say: This is the point of no return, Marty; you've got to make up your mind right now about this facet of the shot! So, you know, that's when you've got to make up your mind."

Scorsese, to pick a side in an endless argument, is America's greatest living director. And yet he still can't make up his damn mind, still gets obsessed, still gets crazed by the same kinds of things that make any creative type nuts. Is he going to get the resources he needs? Will his bosses like what he's doing? Will they give him another chance on another project? How much of his creative vision will get into this project? How much will the powers that be screw with his vision? When does he say "no" to them? When does he say "yes"? Whom does he trust? And how in the world is he going to get away with doing the work he loves for his whole life?

In an era when careers are measured in months rather than decades, Scorsese has reliably delivered for 45 years--but it still isn't easy. "There's always been pressure," he says. "People say you should do it this way, someone else suggests that, yes, there's financing, but maybe you should use this actor. And there are the threats, at the end--if you don't do it this way, you'll lose your box office; if you don't do it that way, you'll never get financed again. . . . 35, 40 years of this, you get beat up." Hollywood has always been a battlefield, as rough as any more-traditional corporate setting.

And yet unlike so many creative geniuses, Scorsese hasn't burned out, he hasn't alienated the people he's worked with, and he's generally not considered a creep. Despite the fact that he's never had a massive box-office hit (Shutter Island is his biggest grosser to date, with $300 million earned worldwide), Paramount decided to give him a reported $85 million to make a 3-D children's movie about a broody child named Hugo Cabret. And while Hugo's success is uncertain (for God's sake, screams conventional wisdom, it's two hours long, it's dark, it takes place in France, and aren't people over live-action 3-D?), Scorsese is well on his way toward funding his next project, Silence--an adaptation of a book about 17th-century missionaries. In Japan! (Which is yet another foreign country, people!)

Of course the spectacles audiences will wear to see Hugo will be a cross between Scorsese's own and the flimsy 3-D glasses of yore. | Photo by Art Streiber

Of course the spectacles audiences will wear to see Hugo will be a cross between Scorsese's own and the flimsy 3-D glasses of yore. | Photo by Art StreiberAny man who can get this stuff financed--never mind make great art from the material--has clearly learned a trick or two. Scorsese has sweated the details of his career as thoroughly as the details of his movies. As he explains here, in his own rat-a-tat style, the man knows a few things about constructing a life of meaningful work--things that apply to anyone in the business of trying to craft a creative life.

RESPECT THE PAST

Nobody talks about the movies the way Marty Scorsese can talk about the movies. His conversation bounds from John Cassavetes (a mentor) to Steven Spielberg (a friend) to Akira Kurosawa (an acquired taste) to George Melies, the silent-film director and innovator whose story forms the basis of Hugo. "When we begin a film," says Dante Ferretti, the Oscar-winning production designer of Kundun, Gangs of New York, The Age of Innocence, and now Hugo, "I read the script and then Marty shows me films. Many, many films, with many different references he wants me to think of for the look of our movie. He carries all these films in his head. He shows me whole films for just one shot, telling me, 'Remember this image, that's the feel I want.'"

Scorsese revels in such details. He likes to speak of directors on three levels: their films, their careers, and their lives within and without Hollywood. He is fascinated by how these men (and the occasional woman) made it--or didn't make it--through the gauntlet. In 1995, he narrated and codirected a documentary about their careers called A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies. It's a career how-to video disguised as the greatest lesson in U.S. film history. Going back to D.W. Griffith, through Howard Hawks and Billy Wilder, and up to modern-day filmmakers, he looks at how these "smugglers, iconoclasts, and illusionists" managed to get some version of their creative visions on-screen. "I was mainly interested in the ones who circumvented the system to get their movies done," he explains in the video. "To survive, to master the creative process, each had to develop his own strategy."

For someone whose own innovations are numerous--the introduction of a certain New York street vernacular in Mean Streets and Who's That Knocking at My Door, the intimacy of the boxing scenes in Raging Bull, the rush and flow of Goodfellas, and now, with Hugo, a reinterpretation or rediscovery of how 3-D can bolster a film's beauty without intruding on the story--Scorsese understands himself as a product of, and a battler against, the Hollywood system. He draws clear lines from classics past to his own work: Nicolas Cage's EMT inBringing Out the Dead is "a modern-day saint, like what Rossellini did in Europa '51"; the fight sequences in Raging Bull draw from, yes, the ballet in The Red Shoes. His comfort with the past is so deep that he romanticizes the old-Hollywood-studio system, where directors worked for one studio churning out at least a movie a year, if not three or four. "There was always a part of me that wanted to be an old-time director," he says, laughing. "But I couldn't do that. I'm not a pro."

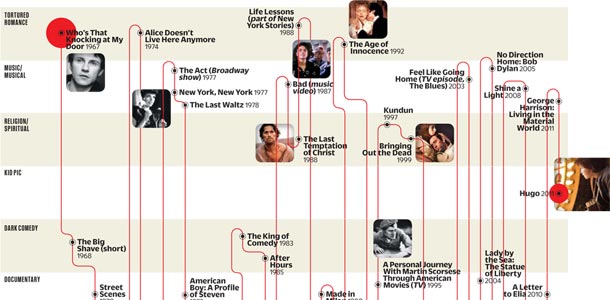

A Man For All Genres

Think Scorsese is just a director of gangster flicks? Think again.

TRUST YOUR CONFIDANTS...

Ferretti is one of Scorsese's trusted advisers at this point, along with director of photography Bob Richardson, costume designer Sandy Powell, casting director Ellen Lewis, and, above all, editor Thelma Schoonmaker. As much as possible, he enjoys working with the same crew. He enjoys working with the same actors, as well. First came Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, and Joe Pesci; more recently it's been Ben Kingsley and, of course, Leonardo DiCaprio; in Silence, he'll turn once again to Daniel Day-Lewis.

"Any great artist needs a lot of support," says Schoonmaker. "We're a group that is totally committed to his high standards, and we understand what he's after." The creative process of a director, unlike that of an actor, is essentially collaborative. And some of Scorsese's greatest creative moments have come about because of suggestions by those closest to him. Watching some early takes on Raging Bull, British director Michael Powell remarked to Scorsese that "there's something wrong about the color of those red gloves." That, says Scorsese, was when he knew the film had to be shot in black and white. When Scorsese was scouting a location for his great Five Points battle in Gangs of New York, Ferretti pushed him toward the CineCitta production facilities in Rome. "We were in Venice talking about this," says Ferretti." We had considered New York, but there's nothing in the city that looks the way it did back in the 1860s. We thought about Canada, but it's too cold. So we decided to go to Rome to check out CineCitta . I loved this idea, since I live here [in Italy]. Before we went, I called up a restaurant, a good one just outside CineCitta, and I said, 'Listen, I'm bringing Mr. Martin Scorsese, and it's important that we eat well. Do you understand me? It's very important that we eat well!' So we went to CineCitta--Marty, Thelma, all of us--and after, we went to the restaurant. And that is why we shot Gangs at CineCitta! I mean, of course there were other reasons . . . "

...BUT NOT TOO MUCH

"There are two kinds of power you have to fight," Scorsese says. "The first is the money, and that's just our system. The other is the people close around you, knowing when to accept their criticism, knowing when to say no." All directors face pressure to make their films shorter, and Scorsese simply cannot deliver a short film. He hasn't made a sub-two-hour movie in 25 years, since the 119-minute-long The Color of Money. For children's movies, the industry standard is to keep it under 90 minutes. Hugo is a two-hour visual feast, with stretches that even some adults at its New York Film Festival premiere screening found taxing. "Some may suggest--how can I put this?--that there's an indulgence on my part," says Scorsese. "But sometimes something needs time to work on a viewer. People talk about length, but it's not just length. It's pacing and rhythm. I've done some of the fastest pictures--the sequences in Goodfellas, and particularly those in Casino, which is a three-hour film that moves very fast."

It's not just a question of ignoring what may seem like completely sensible suggestions. You've also got to know when a collaboration has run its course. "Over the years, people change and they want other things. You've got to understand when a collaborator isn't satisfied anymore," says Scorsese. "Michael Ballhaus--he was a lifesaver for me, an extraordinary cameraman who helped me relearn how to make a motion picture on After Hours. The last picture he did with me was The Departed. It was a very tough picture to make. We had lots of problems with actors' schedules, and I was constantly reworking the script. For The Aviator, the dialogue was very straightforward. But in The Departed, it was not, and with those actors! I mean, that's why you want them, but that doesn't make it easy. So Michael decided he wanted to do other things. That was very sad."

PLAY THE CORPORATE GAME

Sometimes you just have to give in to the system. Scorsese comfortably admits that he made at least two movies for calculated business reasons: The Color of Money, in 1986, and Cape Fear in 1991. The early '80s were difficult for Scorsese. "For a long time," says Schoonmaker, "our films were not recognized and did not make money--which was a serious problem." As much as critics now admire Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and even The King of Comedy, none of those movies ignited the box office. The Last Temptation of Christ had been ginned up in 1983, but six weeks before production was to begin, the studio pulled the plug. Scorsese's follow-up to The King of Comedy was After Hours, a quirky comedy starring Griffin Dunne. The film was shot on budget and on time over 40 nights in SoHo and did fairly well as a low-budget film. But none of that mattered. "They saw me as outside Hollywood," Scorsese remembers. "'You're gone, you're in independent cinema now, on the outside from now on.'"

"There was always a part of me that wanted to be an old-time director," says Scorsese, laughing. "But I couldn't do that. I'm not a pro."MARTIN SCORSESE

Enter The Color of Money. Paul Newman was interested in doing a sequel to The Hustler, the 1961 movie he had starred in with Jackie Gleason. Scorsese abhorred the idea of doing a sequel to anything but says he was intrigued by the character of Eddie Felson: "Again, it was a guy who took too many risks, overstepped the line, didn't understand his own self-destruction, and didn't catch on until it was too late." So he took the job, as a way of proving to Hollywood that he could make a box-office winner. "It was a calculated business move. I needed the new studio heads to think they could give me another chance, finance me again."

Color hit at the box office, and Paul Newman took home the Oscar for best actor. As a result, at least the way Scorsese tells the story, he won the right to finally make his passion project, The Last Temptation. But the tortured production drained Scorsese financially. "I was never interested in the accumulation of money, you know. And I never had a mind for business," he explains. "There have been serious issues with money over the years. I have a nice house now, in New York. But there have been major, major issues. In the mid-'80s it was pathetic, I mean, my father would help me out. I couldn't go out, I couldn't buy anything. But it's all my own doing."

Three confidants pushed him into Cape Fear: his agent, then-CAA chief Michael Ovitz, the best career counselor Scorsese ever had; De Niro, enthralled by the role of Max Cady, the psychotic criminal bent on revenge; and Spielberg. "We were down in Tribeca at dinner," Scorsese remembers, "and I said, 'Steven, I can't do this, I hate the script.' He said, 'Marty, if you did the picture, would the family live at the end?' I nodded yes. So he said, "If that's the case, do whatever you want up until that! And, oh, by the way, this guy over here? He's the scriptwriter. Wesley [Strick], meet Marty.'" He took the movie, with Strick as a willing participant. "We tried to push the genre as far as we could," Scorsese remembers. "We pushed it as good as we could. And I'll never forget the call I got from Ovitz after we'd done it. I pick up the phone and he says, 'Congratulations, Marty, you're solvent! Now don't go screw it up again.'"

DEFY THEM WHEN YOU MUST

In the editing room, in the waning weeks of a production, everything is on the line. The studio pushes harder than ever for the film to satisfy its box-office needs. Actors, through their agents, plead for more screen time. Colleagues have their own ideas, and then there's the despair of the director realizing all the mistakes he made during those precious, long-gone days of shooting. "This is when you see I ain't got certain scenes and I wish I had them," says Scorsese. "Maybe we didn't have the money. Maybe I didn't have time, but if I had chosen to shoot other things other ways, I would have had the time. Whatever--now it's too late. Let's say you make 25 or 30 decisions on a particular scene. If one or two big ones were off, they can ruin everything about that scene. And you only discover this in the editing room."

Photo by Art Streiber

Photo by Art StreiberAt this point, he says, everything is focused on one thing: "What does the film need, what does the scene need?" In every movie, whether a commercial play like The Color of Money or a passion project like The Age of Innocence, "there is an essence to the project that you must protect. You cannot make concessions on that, the story cannot be tampered with past that point; you have to fight off every power or force around you."

This is when Scorsese retreats to a long dialogue with his one constant collaborator, Schoonmaker, who has edited every film of his since Raging Bull. Unlike his other collaborators, Schoonmaker is not a child of the movies. Whereas Ferretti and Scorsese can go on and on about films they watched during their isolated childhoods, Schoonmaker grew up intending to be a diplomat and fell into editing after being chided in the early 1960s by State Department interviewers for her anti-apartheid views. Starting with their time together at New York University, she learned everything she knows about films from Scorsese, who also introduced her to her husband (Powell, the British director). "Thelma stays loyal to me, and to what I'm trying to do with the story, through everything. We'll say anything to each other in the editing room--anything," he says, smiling as he raises those famous eyebrows. "What can be done? What shouldn't be done? If the studio is saying this, maybe what they really mean is this. There are so many issues, it can get very tricky, very political. She'll see me getting tired and giving in, let's say, to someone who has my ear and is very influential, to someone who uses threats. There are a lot of those more and more now, and she will say, 'Be careful, because this is going to harm the whole thing, the whole project.' She gets me back on track if I'm going off."

"Marty knows Hollywood very well," says Schoonmaker, "and he handles them brilliantly. I could never do it. I've heard them say things in meetings--once someone said, 'Why don't you take Gone With the Wind and apply it to this movie?' I swear to God! I would walk out, but he just takes it in stride. His neighborhood prepared him for dealing with Hollywood. And he will fight to the death for a film not to be ruined."

"Thelma and I," says Scorsese, "we think alike in terms of culture and politics. The resistance is always there, that '60s thing we grew up with. Not hippies or anything! I'm not a hippie, not that I had anything against them. We have a way, we can tell when something smells too much of being a part of the process, and we don't want to get too close to that. Sometimes you wake up and you've gone there. But then you move on, watch that the next time you're more careful."

FIND ANOTHER OUTLET--OR EIGHT

Here's a little list of the side jobs that Martin Scorsese, who turned 69 this November 17, has been involved in over the past two years.

1) A Letter to Elia, a doc he directed about film director Elia Kazan.

2) Public Speaking, a doc he directed about writer Fran Lebowitz.

3) Boardwalk Empire, HBO's epic gangster series set in Atlantic City. He directed the first episode and now executive-produces.

4) Living in the Material World, the George Harrison doc he directed.

5) Surviving Progress, a doc he produced, based on the book A Short History of Progress.

6) La Tercera Orilla, a 2012 film directed by Argentine director Celina Murga, who was paired with Scorsese in the Rolex Mentor and Protege Arts Initiative. He will executive-produce her movie.

7) A new Terence Winter project for HBO about a drug-fueled movie exec in 1970s New York; Scorsese will direct the first episode and executive-produce the series (with Mick Jagger).

8) The Film Foundation, which has restored more than 550 old movies and basically salvaged the silent-film era. Scorsese is the founder and chairman--and is personally involved in the restoration of 10 films this fall, including four silents directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

There are two reasonable responses to this kind of list:

1) You should be doing more with whatever creative gift you have.

2) As Tim Van Patten, an executive producer and director of Boardwalk Empire, says: "I don't know how he does it. He's always juggling. I have enough trouble doing this one job and having a life."

This work on the side, especially the music documentaries, has become increasingly vital for Scorsese. "There was a point with The Departed where I was ready to throw in the towel. I wanted to make the movie I thought the script was about, and I thought the studio wanted something else. I figured, Jeez, at this point in my career, I just want to make films where, granted I'll stay within budget, but I just wanna make the movie I wanna make. You're gonna come to me, especially on a project like this, my home turf sort of, and then you're asking for these actors and this kind of movie? I thought this might be the end, just let me out of here and I'm going to shoot the Rolling Stones on stage, that's it."

He did wind up making The Departed, as you may have heard. But since then, besides shooting the Rolling Stones in their most visceral stage performance in decades (Shine a Light), he also directed a great Bob Dylan doc (No Direction Home) and the George Harrison feature. These films are made on a much smaller budget than, say, Shutter Islandor Hugo. But with less money comes more freedom. "When I get frustrated with the commercial playing field of feature films, I go to these movies. I have had the need, more and more, to explore the spiritual or religious. Elements of that find their way into my music films. Music is for me the purest art form. There's a transcendent power to it, to all kinds, to rock 'n' roll. It takes you to another world, you feel it in your body, you feel a change come over you and a desire to live," he says, laughing at his enthusiasm. "That's transcendence." And a far cry from the mundane battles with Hollywood. "The Stones," he says, "working the stage like that at their age, strong and visceral, pure movement and sound and images. That's strong and powerful and defiant."

GIVE BACK AND LEARN

For a filmmaker so conscious of the history of his art, it's hardly surprising that Scorsese is a generous mentor. As Van Patten and Winter were setting up Boardwalk Empire, Scorsese regularly invited them to his offices for screenings. "He's this legend and all that," says Van Patten, "but you get past that instantly because Marty's such a regular guy. Whenever you're with him it's an education. He started us out by meeting once a week, for a double feature or a single movie. He never puts down a film. He'll find something positive about everything. We were watching this one movie called Pete Kelly's Blues [directed by Jack Webb, star of the '60s cop series Dragnet]. After, Marty says, 'Well, this is not Jack Webb's best work,' and I'm thinking, Jack Webb? Really? Does Jack Webb even have best work?' But that's the way he is."

"At this point," says Scorsese, "I find that the excitement of a young student or filmmaker can get me excited again. I like showing them things and seeing how their minds open up, seeing the way their response then gets expressed in their own work." Hugo itself is something of a lesson in film history for kids, with its plot centered around Melies, whose work, which Scorsese has helped restore, is featured in the movie in a run of strange and wild clips.

His biggest teaching project these days is his 12-year-old daughter, Francesca. He's trying to give her a cultural foundation that seems less readily available these days. "I'm concerned about a culture where everything is immediate and then discarded," he says. "I'm exposing her to stuff like musicals and Ray Harryhausen spectaculars, Frank Capra films. I just read her a children's version of The Iliad. I wanted her to know where it all comes from. Every story, I told her, every story is in here, The Iliad."

"Three months ago," he remembers, gesturing to the room around us, "I had a screening here for the family. Francesca had responded to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and to Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, so I decided to try It Happened One Night. I had kind of dismissed the film, which some critics love, of course, but then I realized I had only seen it on a small screen, on television. So I got a 35-millimeter print in here, and we screened it. And I discovered it was a masterpiece. The way Colbert and Gable move, their body language. It's really quite remarkable!"

Thursday, November 24, 2011

What Can I Be Thankful For?

| Q: I've always enjoyed getting together with family for Thanksgiving , but to be honest, I'm dreading it this year. It's been a tough year for me and I don't have any reason to be thankful. I'll put on a happy face and act like I'm glad we're together, but down inside I'll hate myself for being a hypocrite. Have you ever felt this way? -- J.McF. A: I'm sure we've all gotten involved in things we didn't want to do, but sometimes it's better to do them anyway -- not for our sake so much as for the sake of others. This isn't necessarily hypocrisy; it may simply be thoughtfulness. At the same time, I hope you'll take time this Thanksgiving to think of at least five things for which you should be thankful. For example, many people don't have any family to share Thanksgiving with -- but you do. Others struggle with bad health and can't join in their family's celebration -- but you can. Still others are homeless or destitute this Thanksgiving -- but you aren't. You see, when things go wrong in our lives we always tend to focus on what we've lost, instead of being grateful for what we still have. But even in hard times God blesses us far beyond what we deserve, and our hearts should be full of thanksgiving for every blessing He gives us. The Bible reminds us that "Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father" (James 1:17). A thankful heart is a joyful heart. Most of all, thank God today (and every day) for Jesus Christ, who gave His life for our salvation. Is He part of your life? If not, let this become the greatest Thanksgiving you've ever had, by asking Him to come into your life as your Savior and Lord. |

Posted via email from Religion

Roasting The Perfect Turkey

ENLARGE IMAGEPhoto: Todd Coleman

ENLARGE IMAGEPhoto: Todd Colemanby Molly Stevens

As the so-called kitchen professional in my family, I used to be expected to come up with newfangled takes on the Thanksgiving turkey each year. I've brined it, smoked it, fried it, dry-rubbed it; but eventually I (and everyone else around the table) tired of elaborate seasonings and complicated preparations. What we really craved was just a fantastic roast turkey—and this recipe produces exactly that. Follow these steps and you'll have tender legs, juicy white meat, burnished skin, and lots of gravy. In fact, it's the single best technique for roasting a bird that I know and the only one I use anymore when it comes to this special meal.

To start, I shop for a fresh, humanely raised bird, ideally not more than 15 pounds; the gargantuan, industrially raised fowl sold by the truckload around the holidays are bland (at best) and, because they're so big, impossible to cook evenly. One 13- to 14-pound fresh turkey will generously feed 10 to 12 people (for more guests, buy a second turkey). Bring your bird home at least two days before Thanksgiving so you have ample time to presalt, a simple step that keeps the turkey juicy and intensifies its natural flavors.- Begin with the gravy: You'll want plenty of it, so I recommend buying and roasting turkey parts, which will be used to make the gravy's deeply flavorful broth. You'll need five to six pounds of turkey parts —ideally a mix of necks, wings, and legs — to make enough gravy for 10 to 12 people. Ask your butcher to chop the parts into four-inch pieces; smaller pieces are best because the skin and collagen release more easily from the bones, adding flavor and body to the broth. Pat the parts dry with paper towels, arrange them in a single layer in a large flameproof roasting pan (I use the same one I use for the turkey), and roast them in a 450-degree oven, flipping them with tongs after 30 minutes, for an hour total, until nicely browned.

- Transfer the roasted parts to a four- or five-quart saucepan. Don't worry if bits stick; you'll capture them when you deglaze the pan. Place the roasting pan over your largest burner (you can use two burners if that's a better fit), turn the heat to high, and add two cups of water. Bring to a boil, scraping the bottom with a wooden spoon to dissolve any cooked-on drippings, and then pour the liquid into the saucepan. Add enough additional water to the saucepan to just cover the turkey pieces; any more can result in a diluted broth. Depending on the shape and size of your pot and turkey parts, you'll probably need about seven to eight cups of water total. Bring to just below a boil over medium high heat, and immediately lower the heat to a very gentle simmer. Skim any foam or scum that rises to the top, and add

one large coarsely chopped carrot; one large coarsely chopped yellow onion; one coarsely chopped rib of celery; one-half teaspoon of kosher salt; one-half teaspoon of whole black peppercorns, and one bay leaf. It's awkward to skim once you've added the vegetables and seasonings — since they tend to float to the surface — so I don't bother. As long as you don't let the broth boil aggressively, it will be clear. Continue to simmer, uncovered, until it has a sweet, rich turkey flavor, two and a half to three hours. When the broth is done, set a fine-mesh strainer over a heatproof bowl. (If you don't have a fine-mesh strainer, line a colander with a double thickness of cheesecloth.) Strain the broth, pushing gently on the solids to extract as much liquid as you can but not so hard as to mash the vegetables—this will cloud the stock and give it a murky flavor. Let the broth sit on the counter until it cools to room temperature, and then cover and refrigerate for up to four days. Once the broth has completely chilled, remove the layer of surface fat. You can freeze this broth for up to six weeks. In fact, if I'm traveling by car for the holiday, I'll freeze the broth in plastic tubs and use them as ice packs in my cooler.

one large coarsely chopped carrot; one large coarsely chopped yellow onion; one coarsely chopped rib of celery; one-half teaspoon of kosher salt; one-half teaspoon of whole black peppercorns, and one bay leaf. It's awkward to skim once you've added the vegetables and seasonings — since they tend to float to the surface — so I don't bother. As long as you don't let the broth boil aggressively, it will be clear. Continue to simmer, uncovered, until it has a sweet, rich turkey flavor, two and a half to three hours. When the broth is done, set a fine-mesh strainer over a heatproof bowl. (If you don't have a fine-mesh strainer, line a colander with a double thickness of cheesecloth.) Strain the broth, pushing gently on the solids to extract as much liquid as you can but not so hard as to mash the vegetables—this will cloud the stock and give it a murky flavor. Let the broth sit on the counter until it cools to room temperature, and then cover and refrigerate for up to four days. Once the broth has completely chilled, remove the layer of surface fat. You can freeze this broth for up to six weeks. In fact, if I'm traveling by car for the holiday, I'll freeze the broth in plastic tubs and use them as ice packs in my cooler. - Presalting is the key to a juicy bird. Remove the giblets from the turkey, and refrigerate them for later use (except the liver, which you can discard or save for another use). Then pat

the turkey dry with paper towels. Sprinkle two tablespoons of kosher salt andone teaspoon of freshly ground black pepper liberally all over the turkey, spreading a little in the cavity and being sure to season the back, the breasts, and the meaty thighs. If you've never pre-salted before, this may look like too much salt, but it's not. As the turkey sits in the refrigerator, the salt will gently permeate the meat, improving the waterholding ability of the muscle cells so that, when cooked, the meat stays juicy yet does not become overly salty. In fact, when you pull the turkey from the fridge after its salt treatment, the skin will be taut and dry with no trace of salt. Arrange the turkey on a wire rack over a rimmed baking sheet, and refrigerate uncovered (this dries the skin, which helps it turn crisp during roasting) for one to two days.

the turkey dry with paper towels. Sprinkle two tablespoons of kosher salt andone teaspoon of freshly ground black pepper liberally all over the turkey, spreading a little in the cavity and being sure to season the back, the breasts, and the meaty thighs. If you've never pre-salted before, this may look like too much salt, but it's not. As the turkey sits in the refrigerator, the salt will gently permeate the meat, improving the waterholding ability of the muscle cells so that, when cooked, the meat stays juicy yet does not become overly salty. In fact, when you pull the turkey from the fridge after its salt treatment, the skin will be taut and dry with no trace of salt. Arrange the turkey on a wire rack over a rimmed baking sheet, and refrigerate uncovered (this dries the skin, which helps it turn crisp during roasting) for one to two days. - I am a firm believer in not stuffing the turkey: It roasts more quickly and evenly when its cavity isn't filled. I've probably tested every single roasting method out there, from roasting at very high heat to flipping the bird to distribute its juices; none of them surpasses this one, which requires placing the turkey in a very hot oven, then roasting it at a moderate temperature the whole way through. Remove the turkey from the refrigerator about two hours before roasting to take the chill off; this also helps it cook more evenly. Heat the oven to 450 degrees.Tuck the wings behind the neck, and tie the tips of the drumsticks together with kitchen string. Arrange the turkey breast-side up on a rack in a sturdy roasting pan. Pour one and a half cups of your homemade turkey broth into the pan, and slide the turkey into the oven, immediately lowering the heat to 350 degrees. Then let it do its thing, rotating the pan after about one and a quarter hours, for two and a half to three hours total. Meanwhile, combine the remaining turkey broth with the giblets in a two-quart saucepan over medium heat. Simmer gently, partially covered, until the giblets are tender, about 45 minutes. Remove the giblets (saving them to add to the gravy later, if you like), and keep the broth warm.

- For the prettiest, most evenly bronzed bird, baste by spooning pan drippings over the breast every 45 minutes. If you notice the breast or drumsticks getting too dark, cover them loosely with foil during the last 30 to 45 minutes of roasting. Alternatively, if the legs aren't browning —which can happen if the sides of your pan are too high — you may want to flip the turkey so it roasts breast-side down for about 35 minutes and then finish it breast-side up.

- The first hint that the turkey is ready will be the tantalizing aroma that fills the kitchen; you can count on its cooking for about 13 minutes per pound. To be sure, pierce the meaty part of a thigh with a sharp knife, and check that the juices run mostly clear with only a trace of pink—don't wait for them to become completely clear, a sign that the turkey is overdone. To doublecheck, insert an instant-read thermome ter into the thigh, careful not to hit bone; it should read 170 degrees.

- When the turkey is done, grab both sides of the roasting rack with oven mitts to lift and tilt the turkey, and let the juices pour from the cavity into the pan. Set the turkey aside, tenting it very loosely with foil, to rest for at least 30 minutes while you tend to making the gravy. (This resting period allows the proteins to cool and firm up, so the turkey better retains its juices when carved.) Pour all the liquid from the roasting pan into a heatproof bowl or 1-quart glass measuring cup, and set it aside. Set the roasting pan over two burners at medium-high heat, and add three-quarters of a cup of dry white wine or dry vermouth and two tablespoons of brandy. Bring to a boil, scraping with a wooden spoon to dissolve any flavorful cooked-on bits, and return the reserved liquid to the roasting pan. Boil, stirring often, until the liquid is reduced by nearly half, about eight minutes. Turn off the heat, and set aside.

- Once the liquid from the roasting pan has settled, spoon off and transfer the surface fat to a medium saucepan, measuring as you go, to make a roux for your gravy.You'll need about four tablespoons of fat, but every turkey is different, so if you're short add enough butter to make up the difference. Heat the fat over medium-low heat, and whisk in one-third cup of flour until smooth. Cook for about four minutes, until the roux has a light amber color, and then gradually whisk in the reserved pan drippings. Bring to a simmer, and slowly whisk in four cups of warm turkey broth. Let the gravy simmer and thicken, whisking occasionally, for about 15 minutes (or more for thicker gravy). Add more broth if needed to get the consistency you like. For a hearty giblet gravy, finely chop the neck meat along with the gizzard (after removing the gristle) and the heart, and stir this meat into the finished gravy. Season the gravy with salt and pepper to taste, and keep it warm as you carve the turkey. By now, your kitchen will likely be crowded with guests hoping to steal a taste of the big bird. Call everyone to the table, say your thanks, and enjoy your perfect roast.

Posted via email from WellCare